HORSES NATURALLY REACT TO PRESSURE

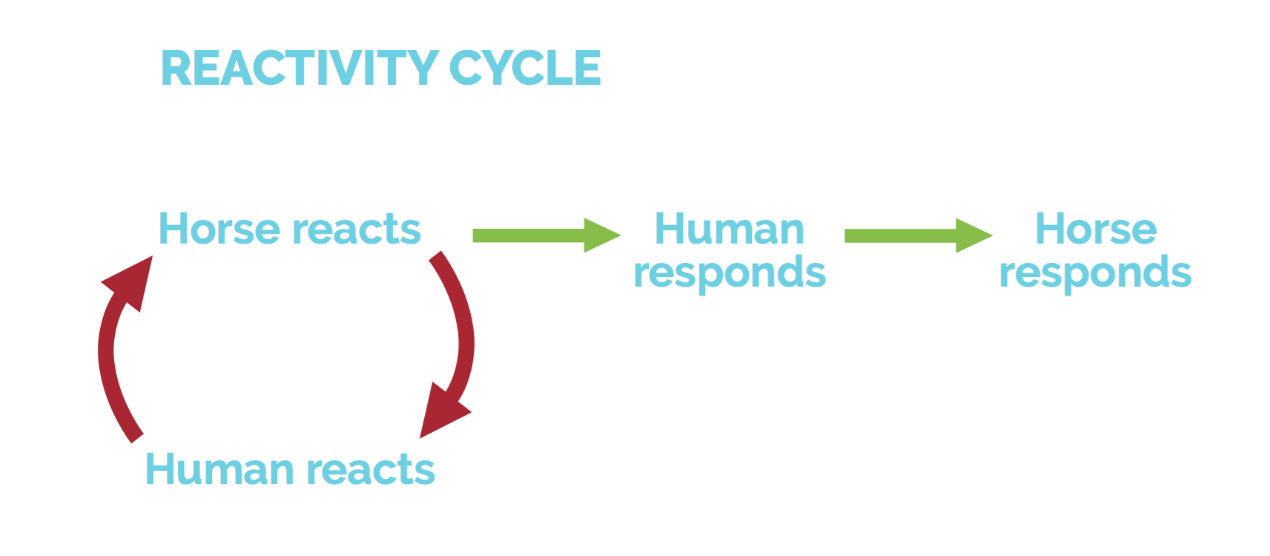

“When we react back, we feed the reaction. How do you break the reactivity cycle? Your job is to master the art of responding, meaning you are “response-able” for and aware of your thoughts and actions. Your job is to short circuit your knee jerk instinct to react back, which will keep you and your horse stuck in the same old cycle.”

The Art of

Responding

- Listen with empathy. In other words, attempting to see your horse’s real reasons for reacting: survival. We will talk about listening with empathy in this section.

- Validation to build trust. Validation is about honoring the horse’s fear and showing him you understand his experience by taking action, simplifying the behavior. This includes increasing the horse’s tolerance for pressure over time. By doing so, you can avoid full-scale reactions (if any at all). These are covered in depth in Rules #3 & #4 in my 5 Golden Rules.

Step #1: Listen With Empathy

In his book, A Course in Miracles, David Hoffmeister says, “An untrained mind can accomplish nothing.”

Similarly, proponents of advanced emotional intelligence, such as Jesus, Buddha, Martin Luther King Jr., Ghandi and many others taught people to practice resisting the fight-or-flight impulse in favor of the tend and befriend philosophy.

The danger of reacting back to another’s reaction is that a self-perpetuating cycle is created—you hurt me, so I’ll hurt you. When you react back, you feed the reaction. Like a continuous game of ping pong, it gains momentum and escalates in violence. As Ghandi put it, “An eye for an eye will only end up making the whole world blind.”

The only way to break the cycle or stop it from occurring in the first place is to respond from a place of love. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

“By seeing through the lens of love, we can understand that only hurting people hurt people; In other words, people who have an open wound inflict their pain onto others in an attempt to feel relief.”

Thus, a requirement for empathy is this: Know that everyone is simply trying to survive. You don’t have to like everyone or agree with them, but know you share the same struggles. Every second of the day, we are trying to survive both physically and psychologically. Every thought, choice, and movement is meant to preserve our existence. Every inconsiderate, violent and seemingly hateful action are strategies to minimize pain and chances of death while holding onto life. When someone reacts, they are revealing to you their deepest fears and vulnerabilities. Recognize this as a call for love; the wild horse inside them crying out in fear.

With this understanding, we can respond with compassion rather than another reaction that feeds their own. With love, we can stop the cycle.

“This concept applies in the same way with our horses. The wild horses have taught me that every reaction—fight, flight, or freeze—that the horse offers is fear based. I must understand this in order to respond with compassion—calmly and patiently—to bring about a positive change in the horse.”

In other words, this understanding leads to compassion and the compassion is what allows me to respond in a way that allows me to help guide them through that fear rather than react back and feed the cycle.

When we diagnose the cause of the horse’s behavior as a lack of respect, however, we react back to the horse out of fear, demanding respect. This causes the horse to react back with more fear, causing us to react again and the cycle continues. Eventually the horse either submits out of fear and shuts down emotionally–at which point they are labeled as trained–or becomes so anxious or aggressive that they are labeled as untrainable.

When we diagnose the cause of the horse’s behavior as a result of fear, we respond from a place of understanding that allows us to act with compassion. From this place, we are able to respond to the horse’s reaction in a way that guides him from a place of fear to a place of understanding. Once he understands what the pressure means and how to respond to it, the fear is gone and so is the reaction.

Step #2: Validation Builds Trust

So if we don’t react back to the horse’s reaction, how do we take action and respond to the horse’s reaction to ultimately teach him to respond as well?

From a scientific perspective, teaching the horse to respond in a calm and relaxed manner to pressure involves literally rewriting the script in the mammalian brain and creating new connections and neural pathways. That means we have a large task at hand—we must reboot how the horse navigates through his environment. Our job is to teach the horse to respond to pressure, which we can accomplish through the use of negative reinforcement, or using a humane onset of pressure to motivate him to find the release. How does this work?

In traditional practices, when a pressure is introduced (mental or physical), we must continue with the pressure until the animal offers the smallest sign of responding versus reacting. At that moment, we must release to reward the animal for thinking through the situation.

Consider a horse who reacts to touch on his legs by kicking out, which is a natural survival instinct. If the human releases the touch on his legs at the moment of the reaction, the instinct is reinforced. But by continuing with the mental pressure of touching his legs until he stopped kicking for just a moment, the human is able to offer guidance through the situation and reinforce the behavior of responding to that pressure. Over time, he will be able to approach a wider range of new situations by responding instead of a reacting to the trigger.

“This method can be effective, but it has its limits. This is due to the fact that it is missing an essential component: Validation.”

Take a moment to consider a child who has a case of “monsters-under-the-bed-syndrome.” What is the typical response when a child is frightened by the ‘monsters?’ Oftentimes, the adult’s response is something like, “Don’t cry! Monsters don’t exist, there is no such thing!” And so, the child’s fears continue, night after night. This is an example of invalidating the child’s feelings—we communicate that the child is not right for feeling what he is feeling.

The anecdote to the child’s fear is the opposite—Validation. Validation means taking time to express that you understand another’s experience in that moment; that you understand why they are feeling what they are feeling, not as if their experience is bad, wrong, or crazy. Many times all the child wants is to be heard and understood; to have their fear honored rather than rejected. They don’t have the words to be able to articulate that the fear of abandonment (a dependent child’s greatest survival threat) arises at nighttime; instead, the monster serves as his voice. It’s just what makes sense to them.

The method described above, to teach the horse to accept touch, encourages us to operate from our first instinct to a reaction, which is to tell the horse how he or she should be acting, feeling or thinking, thereby invalidating the horse’s position so that we can feel in the right. This takes priority over helping the horse to feel understood. It’s like telling him, “Well I see you’re scared but there’s nothing to be afraid of, there are no such thing as monsters!”

Validation can immediately soothe negative arousal. When people (or horses) are on the defensive they are in a negative arousal state; they are physically preparing to go into fight or flight. When in this state, knee jerk reactions are almost uncontrollable. However, validation strategies soothe fight, fight, or freeze reactions. When the horse or human feels understood, there is no need to go into battle.

“When you validate others, you let them know you really understand them. You let go of your own agenda and be attentive to their experience and needs. In this way, you help the other feel as if his or her experience is understandable, not bad, wrong, or crazy.”

The alternative then, it validate how the horse is feeling and acknowledging the monsters! How do we provide validation to our horses? You don’t have to agree with their reaction—You know a plastic bag isn’t going to kill them. But you do have to let them know that you understand their experience in that moment. Instead of telling the horse they are wrong for experiencing what they are experiencing, you open yourself up to understanding it. This is what opens communication up. Validation lets two individuals truly communicate about the root of problem rather than resort to attacks or defensiveness.

In Rule #2 of my 5 Golden Rules, I cover in depth how to allow the horse the freedom of choice, thereby validating the emotions that come up during a behavior. The horse will have the freedom to actively participate or to communicate when he feels ready to start a behavior or feels it needs to end. This is accomplished through two way communication, the redirection technique (when using positive reinforcement, reward based training), and the win-win situation (when using negative reinforcement, pressure and release). In Rule #3, you will learn to read a horse’s precursors for reacting and stay out of the reactivity zone and in Rule #4, you will learn how to gradually increase the horse’s tolerance for pressure.

Solving A Puzzle

Using these tools, you will be teaching the horse to respond versus react to pressure without necessarily having to put the horse through a reaction. In other words, you teach the horse to accept touch on the leg without kicking out without him necessarily having to kick out to learn not to show that behavior. The process—when done well—is incredibly smooth.

When a horse has truly mastered responding and thinking through all types of pressure, even in high-pressure or seemingly dangerous situations, he will approach every situation like he is solving a puzzle; this behavior will be defined by curiosity, engagement, relaxation, confidence, and willingness to think through the pressure logically. In turn, such behavior will keep him safe in a modernized world, which poses new risks that require a new form of thinking.